Bad Brands, or just Bad Management?

“Brands are finding it hard to adapt to an age of skepticism,” The Economist declared a couple of weeks ago. “Brands have never been more fragile,” James Surowiecki agreed in The New Yorker. I don’t buy the story. In an age when consumers suffer under ceaseless blather and excessive choice, brands matter more than ever–unless their owners devalue them.

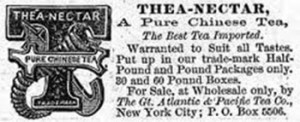

In my book The Great A&P, I wrote about one of the very first brands, a tea called Thea-Nectar. It was introduced in 1870 by The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, which operated a chain of tea stores and also sold teas by mail. The company’s challenge was that its young hyson and Souchong teas, sold loose by the pound, were identical to the teas sold by others. Thea-Nectar, by contrast, was sold prepackaged, in half-pound or pound boxes with a picture on the front. It was said to be a unique mixture of teas that were dried on porcelain, with no coloring or impurities. Thea Nectar was a hit, throwing the tea trade into turmoil and helping the Great Atlantic & Pacific distinguish itself from dozens of competing tea companies.

The arrival of other branded products from companies such as H.J. Heinz and Kellogg allowed grocery stores to offer something besides bulk products. It also permitted chains to prosper, as they could take advantage of volume discounts in dealing with manufacturers. By the early twentieth century, the Great A&P was already using store brands to segment the market, offering its customers a choice of good (Iona lima beans), better (Sultana lima beans), and best (A&P lima beans). House brands like Ann Page and Eight O’Clock Coffee became powerful tools for drawing shoppers into A&P’s stores.

Obviously, a few things have changed since those days, and the new case against brands is that consumers don’t need them. Once, brands stood as guarantors of quality, the argument goes; now, however, consumers can check reviews online before they go shopping, so brand names are no longer necessary to provide a signal of quality.

I think that analysis is off base. Brands lose value not because consumers no longer want them, but because managers abuse them. Let me offer a few examples.

One is Sony. In the 1980s and early ’90s, Sony’s Trinitron TVs were among the best on the market, and were priced accordingly. Sony tried to extend its brand into personal computers, which it sold at a premium price. Unlike its TVs, though, Sony computers were not demonstrably better than other computers. Sony might well have built a successful business by selling its branded machines at the same prices as its competitors, picking up volume that would allow it to lower per-unit manufacturing costs. But rather than offering a name brand at the same price as a no-name, its managers persisted in charging a premium price without offering a premium product. Consumers walked away.

A second example stems from the recurrent cases of salmonella in ground beef, which have caused numerous illnesses and too many deaths in recent years. In one of those episodes, a couple of years ago, it was revealed that beef suppliers’ standard contracts with supermarkets prohibited the retailers from testing for salmonella. I understand why a meat processor would propose such a contract, but I don’t understand why a retailer would sign it. It’s in the retailer’s interest for shoppers to assume that it goes to extra lengths to sell only high-quality merchandise. For a retailer to admit that it cannot monitor the quality of the goods it sells is to tell customers to look only at the price, which in general is not a wise business strategy.

A third example concerns a shoe manufacturer, for whose products I used to pay dear. One day I was in its store and found men’s dress shoes, made in China, selling for $49 under the same brand name as the $250 shoes I was contemplating. Naturally that set me to doubting the quality of the $250 shoes I was about to buy. I left the store. I still by brand-name shoes, but from another company that does not bestow its brand on cheap shoes from China.

In each of these cases, the issue was not that the brands lacked value, but that their owners succeeded in devaluing them. The same, unfortunately, has been true of A&P. The company is still around, but after decades of mismanagement it has pretty much destroyed the value of its brands. The giveaway: at most of its stores you’ll be hard pressed to find the A&P name on a single product, much less above the door.

Tags: chain stores, discounting, retailing